10 Sep What Are Stereographs?

Did you have a View-Master when you were a kid? It was a little red binocular box you held up to your eyes while facing a light. When you pulled the side lever, an image popped up in the viewer. I don’t remember owning one, but I do remember watching Mickey Mouse fly across my vision as I rapidly pulled the lever. This little plastic toy and circular negative boards came from an 1839 invention called a stereograph.

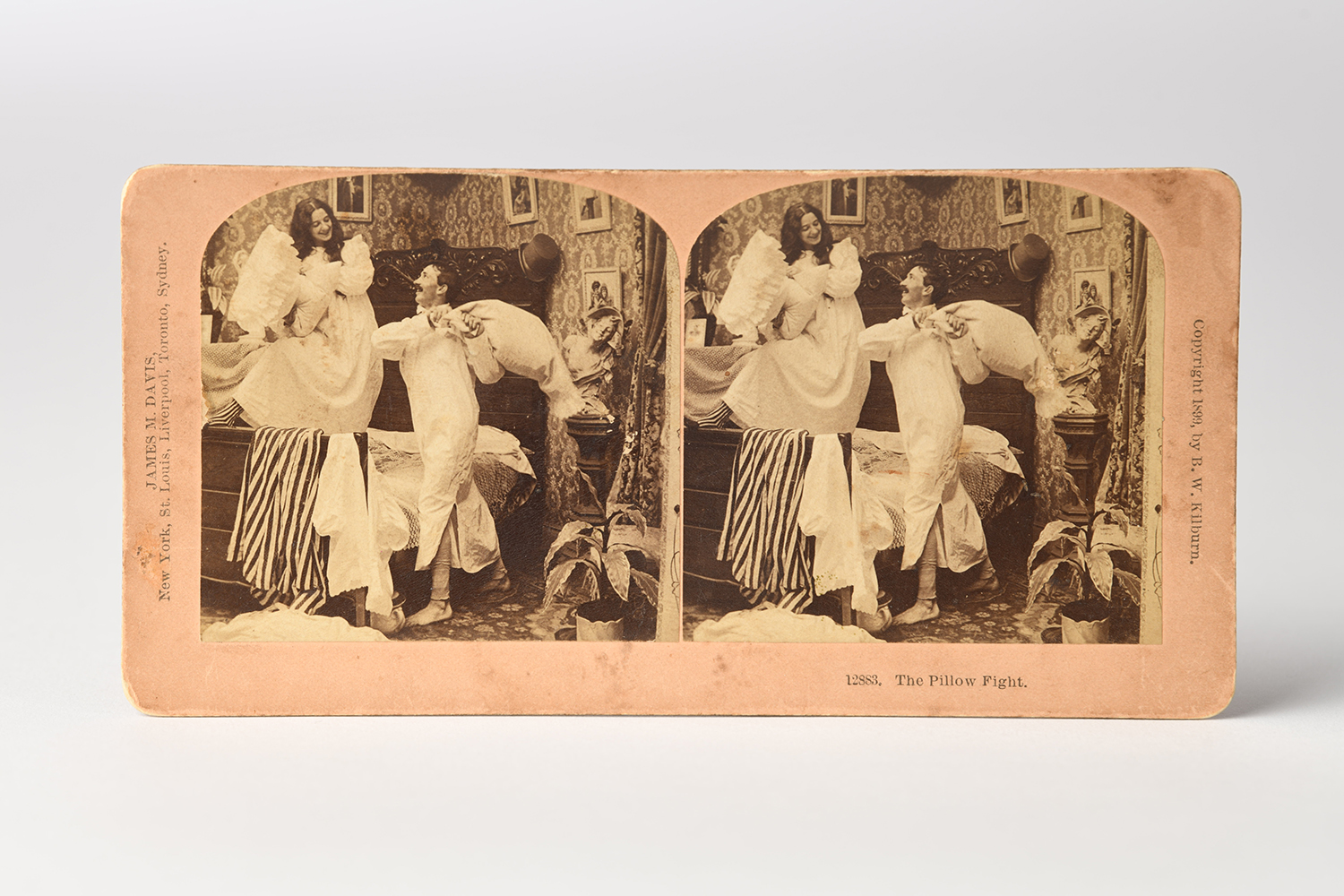

A stereograph image is “two nearly identical photographs or photomechanical prints, paired to produce the illusion of a single three-dimensional image, usually when viewed through a stereoscope.” Artists didn’t view the images as “art” per se, but that didn’t matter to some photographers and printers. Collected by the middle class in the late 19th century, stereographs were a popular photographic commodity that helped cement photography’s spot in our society.

How did the stereograph become the View-Master? Let’s take a look.

Stereographs: A History

Like Talbot, Daguerre, and Herschel, Sir Charles Wheatstone was an early inventor of photography. He used talbotypes (calotypes) to make the first stereograph images in 1839. Naomi Rosenblum writes that some early stereoscopes used daguerreotypes to create a three-dimensional effect. It wasn’t successful because the metal surface often interfered with the image. Other stereoscopes were printed on glass and paper chemistry. According to Beaumont Newhall, this type of photography didn’t become practical until 1849 when Sir David Brewster created a stereoscope viewer that was easier for someone to hold and manage.

Photographers created early stereographs by moving the camera a few inches in one direction or moving the plate holder. In 1856, John Dancer debuted a twin-lens stereoscopic camera, which made this type of photography easier to capture. He believed the “lenses should be the same distance apart as the human eyes.” Other manufacturers built off of this design and continued improving the stereoscopic camera through the 20th century.

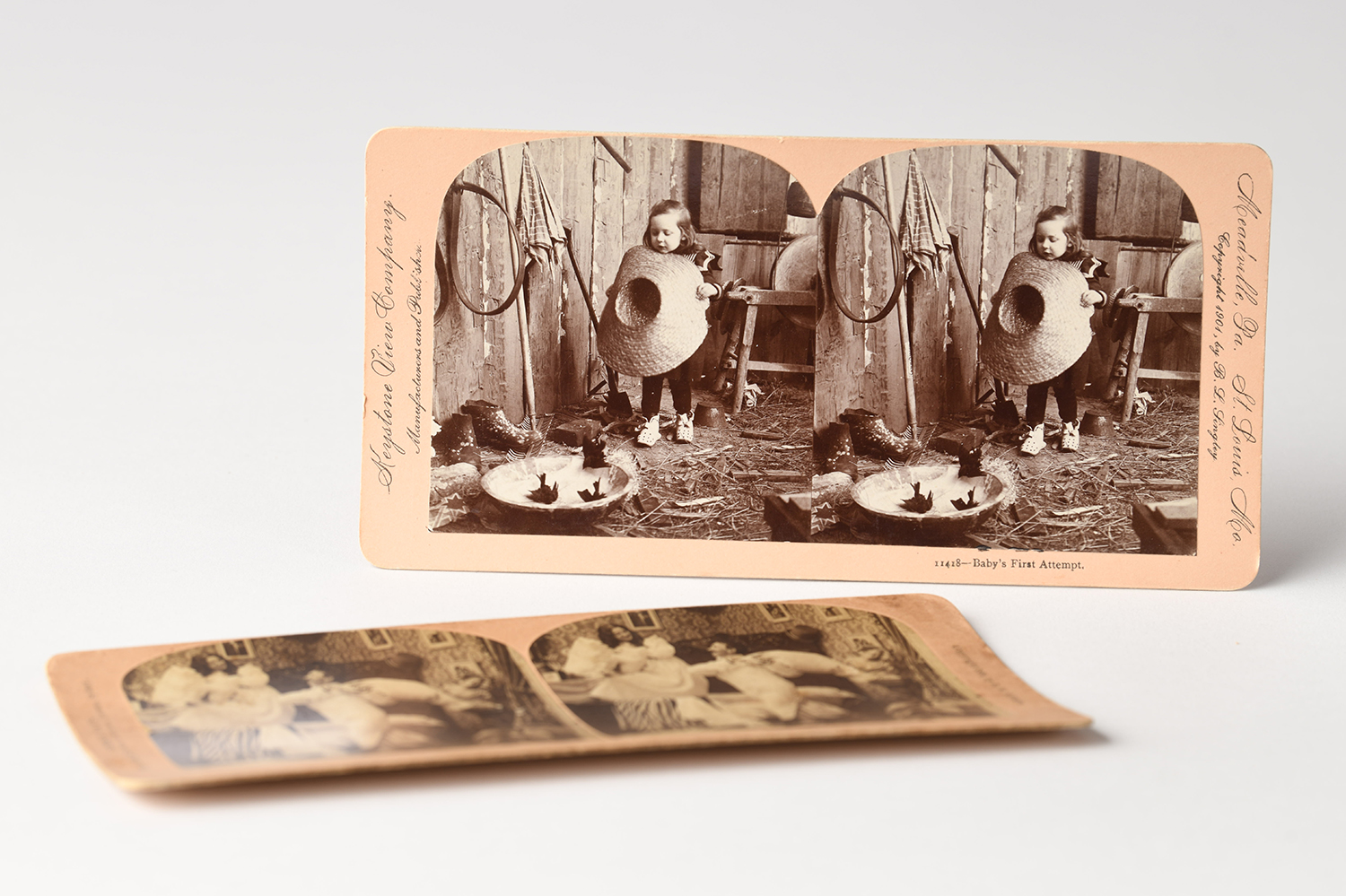

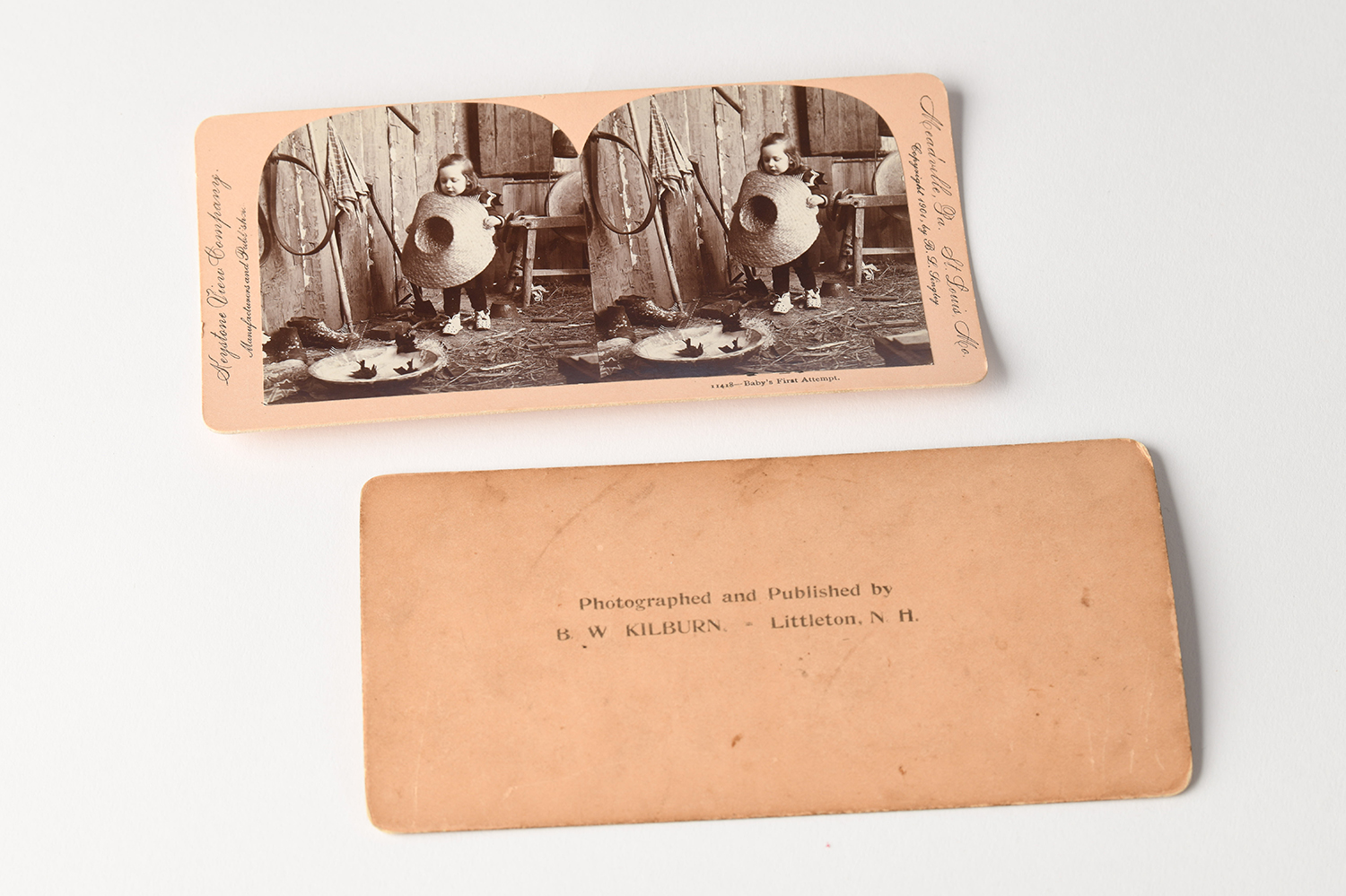

Mass-produced stereographs took the middle class by storm. Printers created the photographs using “steam driven machinery and mounted [the photos] on cards using assembly methods.” These images usually have a caption underneath the photo or on the back of the image to give context or commentary to the viewer. On the back, you may find the photographer’s information, series number, or other relevant information to the photo or the printer.

Collecting Stereographs

This widespread availability and mass production caused a collecting mania between 1870 through 1920. You could buy these images in stores, by mail, or through door-to-door salesmen. Rosenblum notes that the middle class collected stereographs depicting:

- Landscapes

- Views of monuments

- Scenes of contemporary events

- Educational images

- Reproductions of art

- Illustrations of songs and anecdotes

These images provided “entertainment, education, propaganda, spiritual uplift, and aesthetic sustenance.” Stereographs exposed 19th and early 20th century viewers to different experiences and cultures without leaving their homes–much like today’s television and internet. According to the American Antiquarian Society, they were so popular that people believed “libraries devoted exclusively to stereographic images would have to be constructed.”

Of course, this didn’t stop people from criticizing the stereograph. Photographers didn’t always get credit for their work, and images weren’t always politically correct. Artists didn’t consider the stereograph to be an art form. These images were too mass-produced and too close to reality for their taste. In their opinion, a photograph was supposed to create an “impression of nature.” As Newhall writes, “It is an image, not a picture.” However, this didn’t stop the public from enjoying the medium. They continued to collect stereographs well into the 20th century.

The Stereograph Today

Stereographs fell out of fashion when movies and television took over the public interest. By the 1940s, manufacturers used stereographic technology to create ophthalmic equipment–a technology we still use today. Two popular brands, Tru-Vue and View-Master, rebranded stereographs into children’s toys that were household staples from the 1960s through the 1980s.

Today, we still use stereoscopic cameras. You may not know you use them; they’re called 360 or 3-D cameras. Professional and amateur photographers use them to capture their adventures, travels, real estate, etc. Google Cardboard is an example of a low-tech version of a stereoscopic viewer. All of this creates a virtual reality experience. You can tour a home, visit a city, or snowboard down a mountain without leaving your house. How Victorian!

If you have a vintage stereograph, you need to treat it with care like any other antique photo. To prevent fading and damage from silverfish, dust, etc., store stereographs in a cool, dry environment in a museum box or archival sleeve. Some stereographs are curved by design to help the 3-D effect. Do not try to flatten them. You will cause them to snap or tear. This will ruin the integrity of the piece.

If you’d like to see a stereograph in action, then you’ll love The Royal Collection Trust website. They created 3-D animations of a few antique stereographs. They use modern technology to help us experience this fascinating product of photography history. It’s always interesting to see which pieces from the past influence our modern technology. I doubt early stereoscopic photographers or little kids in their living rooms with their View-Masters would ever imagine that the product they held would make such an impact on the world.

Interested in photo storage? Check out our article, “Getting Started: Photo Storage.”